You’ve had a long career as a physician. How have you incorporated art into your life?

When I was a physician I pursued plein air painting in oil and watercolour during holidays to various places like the Adirondack Mountains of New York where my in-laws lived and Cliff Island where my mother's family has a cottage.

Additionally, my wife and I would sail to other island destinations with our three sons. They were young and tolerant of being on a boat for three hours at a time as long as they could disembark to play on the beach or woods. We often visited Monhegan, the destination of many famous painters, including Edward Hopper, Robert Henri, Andrew Winter, and Jamie Wyeth.

Eight years ago I was introduced by another artist in my community to a widow. Prior to my meeting her, for 30 years she and her husband had come from Switzerland and visited my hometown. She continued visiting after he passed. We’ve managed our relationship through Skype and my visitations to Switzerland several times a year prior to Covid. Over the past eight years, I have encouraged my companion, an existential gestalt psychotherapist, to explore through painting what she feels in her personal life and responds to visually.

Although I’m currently not painting on canvas or panel I receive much satisfaction from analyzing the work of painters past and present that I respond to. I share with my companion what it is I appreciate and have learned from studying the techniques and composition of other artists.

How did you get started working with salvaged and found wood?

Many of my patients were local artists. We would discuss their artistic pursuits and art in general during their visits to my office and when we met socially beyond the confines of my office. One of my patients ran the boatyard Hodgdon Yachts.

Each Friday wooden remnants were put into a dumpster when the shop was cleaned out each week. I would collect interestingly shaped pieces of wood, mostly teak and mahogany. I collected these materials intending to do assemblage work later on.

I did not do assemblage work until the last years of my professional life as a physician. As is often the case with ageing artists, early macular degeneration started affecting my ability to appreciate other artists’ work and scrutinize my own work. This has resulted in an increasingly greater connection to impressionistic work where reductionism distils down the essence and bare essentials necessary to represent and convey what I feel emotional and what I perceive as necessary at the most basic level for the viewer to share in my visual experience.

When I retired at 65, the boatyard, run by generations of Hodgdon’s, went out of business. The source of my materials dried up. At that point, I turned to discards from local furniture makers and broken furniture from a local recycling centre for interestingly shaped wood that could be reclaimed.

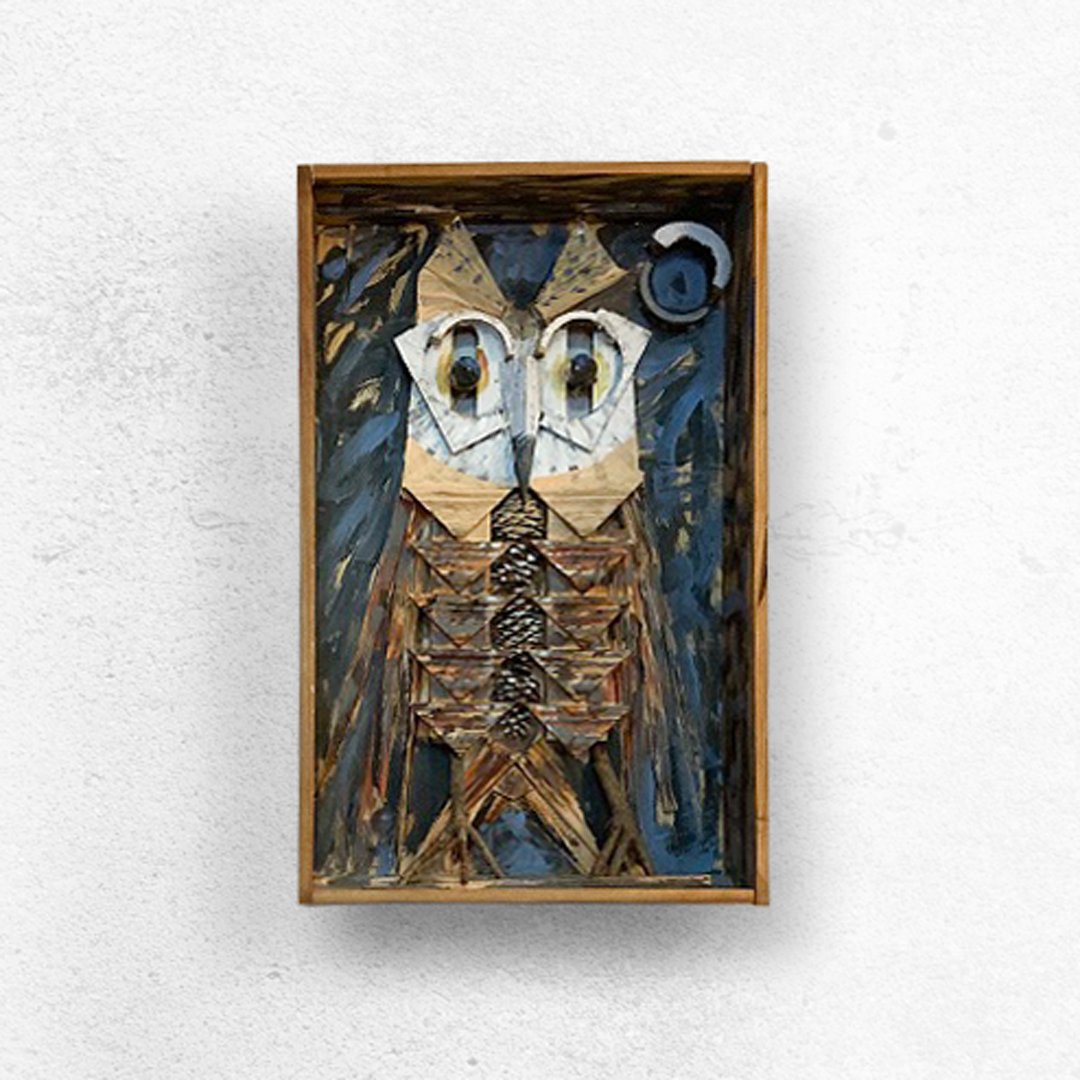

When I first came to Switzerland and attempted to stay involved with my work as an assemblage artist, I found there to be a paucity of repurposable materials that I was accustomed to using. In Switzerland, nothing unused or unwanted can be found just lying around, which I think is consistent with the orderliness and commitment to maintaining the ambience for which Switzerland is known. For that reason, some of my earlier work in Switzerland was composed of pinecones and the interior cradling of wine crates that were disassembled.

Where is your art studio?

In the last years of my professional life as a physician, I constructed a 9x9 metre barn studio on my property where I now store my materials and exhibit my work. On the island where my family has a cottage, I have a small studio that I go to during the summer. I often produce work using pieces of driftwood that have come ashore. I marry the driftwood with reclaimed wood remnants from the local furniture makers and recycling centre.

The type of work I do really requires me to be isolated and focused. It is not something that I do with an audience, though I do plan to go into the local school system in the coming year. I’ll demonstrate my work, and I’ll also lead a workshop. Two separate groups of students will be given similar pieces of wood to experiment with. This will demonstrate how even if one begins with similar materials, entirely different representations can result.

The subject matter of your sculptures varies widely—from wildlife and portraiture to idyllic landscapes and politically charged issues. How do you decide upon the subject matter and derive titles for your pieces?

As a plein air painter, I never titled any of my work. I simply indicated the location on the back of the frame or panel. Assemblage work however lends itself to titling. Those titles arise from childhood remembrances such as Dr. Seuss’s characters, e.g., Cindy Lou Who in How the Grinch Stole Christmas. Sometimes creating ambiguity or a play on words with a malaprop or word reversal, draws a subliminal response from the viewer.

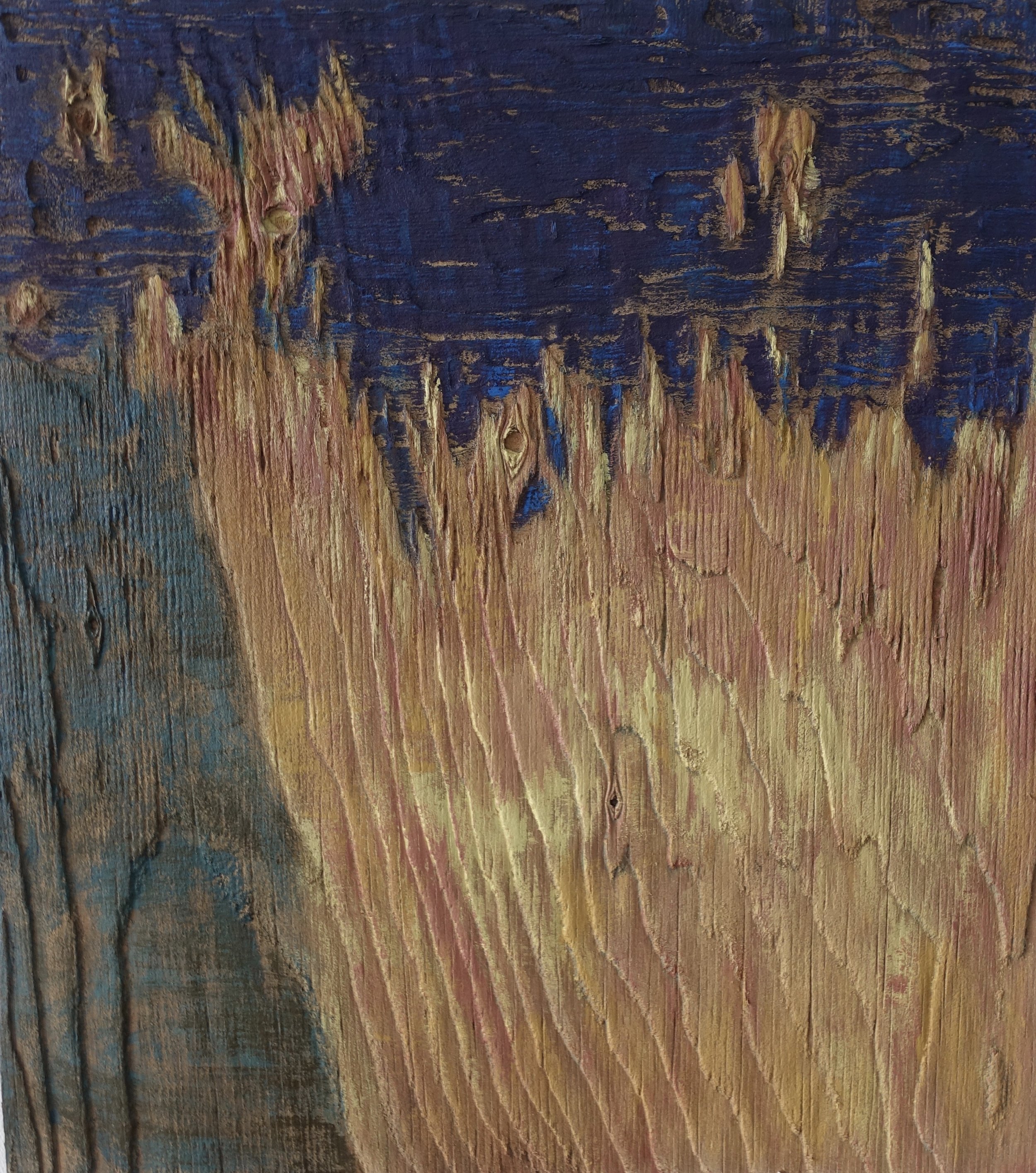

Often the shape or texture of materials that I’m working with defines a title. The textural background of a wood panel I found resembled a fiery landscape and later became my piece Ablaze. It’s a coincidence that there were incessant forest fires on the West Coast of the United States. Lost Family was one of five Ukrainian pieces I created in support of humanitarian aid to Ukraine. I have a strong affinity for the maritime history of the Northeast coast of the US. In Lost in the Fog, the two men in a dory are emblematic of times gone by.

What are you currently working on?

Yesterday, I gathered together a bunch of sickles with wooden handles. Gathered together, with the blades facing in the same direction, I felt that they looked like the shock of feathers on the top of the kingfisher, a local sea bird. With that idea in mind, I'll find pieces of wood that I could use to complete the bird’s head.

Do you think you will keep working with assemblage or switch to another medium in the future?

I plan to continue doing assemblage work. My work stands out to gallery owners who seek to offer their clientele something unusual, three-dimensional, does not need to be freestanding, and can be hung on the wall. With there being so many painters it is much easier to get into a venue.

What about assemblage still challenges you after all these years?

When painting on a flat surface the three-dimensional challenge is in creating depth and perspective. With assemblage sculpture, the three-dimensional challenge is durable attachment.

Over the years, moving art from one place to another and leaning pieces against each other, inadvertently aspects of sculptures may be struck or otherwise detached by pressure against protruding segments. Having to do warranty work on a sculpture is an infrequent occurrence, but the spectre of having to do it gives us one pause to ensure that vulnerable pieces are glued and their attachment reinforced with screws from behind. Trying to avoid repair work of any kind makes one rethink materials, manner of attachment, and composition of representation.